Moths

Is it a bird, is it a butterfly, is it a drone? What on earth is this exotic creature visiting your garden on a hot summer’s day? It buzzes like a bee, zigzags rapidly from plant to plant, helicopters away and then zooms back again, hovers over flowers like a humming-bird … Ah, there’s the clue – it’s a humming-bird hawkmoth. This super-moth defies all our preconceptions about moths. It is active by day. It can fly fast, with a top speed of 12mph. It migrates here from Europe, just as our summering birds do. It has a proboscis (tongue) an inch long, which it inserts deep into flowers to sample their nectar. And to do this with the necessary surgical accuracy it has to hover, immobile, in front of each bloom by beating its wings at an unimaginable 80 times a second. You then also see its showy colours, with the orange flash on the whirring hindwings transformed into a glowing blur. No wonder the novelist Virginia Woolf described this summer sprite as a creature of ‘tremulous ecstasy’.

The whole hawkmoth family is very striking. Their caterpillars were thought to resemble the ancient Egyptian sphinx, hence their scientific name Sphingidae. Among these, the hummer, as it affectionately known amongst naturalists, is one of the few moths familiar and recognisable enough to have garnered traditional folk names. Their old country nickname in English was ‘merrylee-dance-a-pole’, while the French called it variously fleuze-bouquet (flower-sniffer’), saint-esprit (‘holy spirit’) and bonne nouvelle (‘good news’). Hummers have in fact long been thought a good luck omen and there is a story one would like to believe that on D-Day, 6 June 1944, a small party of them was seen flying over the Channel from France heading for England. In recent years they have been getting commoner and it is believed that a few of them now overwinter here, to emerge from hibernation in the spring. A very welcome addition to our native wildlife, if so.

The favourite food plant of their caterpillars is lady’s bedstraw, while the adult moths are especially drawn to flowers like lavender, verbena and above all red valerian – all common here. When they find a flower-bed they particularly like they exhibit another remarkable ability known as ‘trap-lining’, after the practice of trappers visiting their line of traps at regular intervals and in a fixed sequence. The hummers return to exactly the same patch of flowers at the same time each day, demonstrating an excellent visual memory for particular colours, routes and locations. Check it out yourself. You may have heard of song-lines and ley-lines – let’s plot our local hum-lines.

Jeremy Mynott

4 May 2023

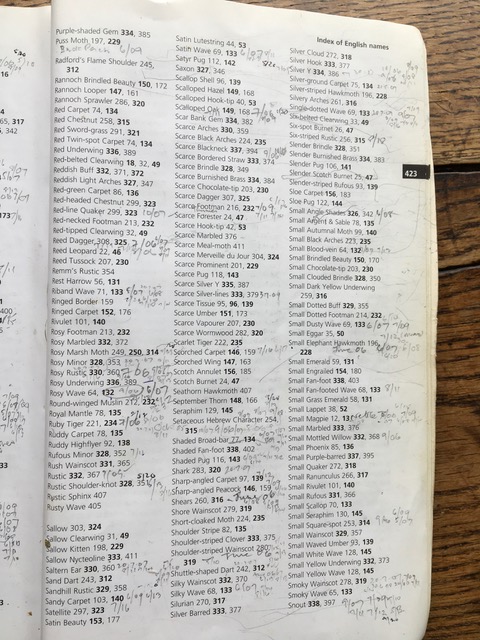

I have in my hands a wonderful book. It was a treasured possession of long-time Shingle Street resident, Tricia Hazell, whose life and memory we recently celebrated. The book is rather battered and weather-beaten (like the rest of us), but has been honoured by years of constant and loving use. Over twenty years use, in fact, as I can deduce from the spidery annotations in Tricia’s hand over lots of the pages. It’s her moth book, a field guide with her dated records of the many moth species that visited her secluded garden at the southernmost end of Shingle Street.

Tricia would often invite over local moth expert Nick Mason and myself to set up an overnight moth-trap and then early next morning inspect the host of bejewelled beauties that had taken refuge there, before releasing them safely into her garden again. Sometimes we’d invite over a larger group of residents to share the experience and the event would take on the character of a moth-séance, with an attentive circle of devotees gasping reverentially at each new winged spirit summoned up and announced by Nick as our moth-medium. Thinking of them as spirits isn’t a bad analogy, in fact. In the ancient world moths were thought of as ‘souls’, which were released from one’s body at the moment of death to flutter away and disappear into thin air. They continue to be magical creatures of the night, whose presence amongst us feels like an epiphany.

One thing that impressed me about Tricia was that she wasn’t, like some naturalists, just interested in identifying the moths and keeping a tally of them. She asked other sorts of questions, too. Whenever we extracted a new specimen from the box she would carefully note the date we’d seen it, but then insist that we pause so that she could discover in her field guide what specific habitats it was found in, what food plants it preferred, and what time of year it would typically emerge. For example, we’d learn that the gorgeous Small Elephant Hawkmoth we’d just caught could be expected ‘between May and July’, was ‘largely coastal’, had a particular liking for ‘heathlands and shingle beaches’, and was attracted to ‘viper’s bugloss, valerian and honeysuckle’. ‘Well, that all fits perfectly’, she’d conclude cheerfully. Although she’d be amazed to hear me say it, Tricia was an ecologist. The word ecology literally means the study of wildlife in its ‘home surroundings’ – that is, in its relationships with the whole web of life on which it depends. And the mark of a good ecologist is not how much you know but in asking the right questions.

Jeremy Mynott

30.3.23

The exciting thing about this time of year is that one keeps seeing the ‘first’ of various things for the year: the first butterfly (usually a floppy yellow brimstone butterfly gliding along a hedge), the first chiffchaff (freshly in from Africa), the first frog spawn (in your garden pond – you should have one if you don’t already), the first bumblebees, the first shoots of green on the hawthorn, the first cowslips in the banks, and so on. I still feel a jolt of adrenaline when each of these appears again, a reassurance, as the poet Ted Hughes put it, ‘that the world’s still working’. More than just a reassurance, though. It’s a joyful sense that the dark days of winter are soon to be replaced by light, warmth and growth. A feeling of abundance and renewal. Who wouldn’t feel the emotional sap rising at such a time?

But it’s getting more complicated, like the rest of life. This ‘spring’ we had the first sticky buds on the chestnuts in January, and the first aconites out in December; there’s been a chiffchaff flitting around all winter; and I’ve just seen my first brimstone, like a floating piece of detached sunlight. Isn’t this good news? It can’t be bad to enjoy the pleasures of spring a month or two earlier, can it? But suppose we are losing the familiar distinctions between the seasons altogether? These are deeply ingrained in our history and culture, and give us our bearings in the natural world. I wouldn’t want a bland, uniform climate in which the cycles of growth and rebirth had been flattened out, even if it was a bit more comfortable.

We’ve got used to this kind of thing in our eating habits, of course. You can now eat fresh raspberries all the year round. And you can buy exotic fruits like avocados at any supermarket or corner store. I don’t suppose I had ever eaten an avocado until I was 30, and if you had asked me as a boy what the word ‘Avocado’ meant I might have guessed at some sort of Church prayer or Mexican board game; but at this rate we may one day see avocados growing in our own back-gardens.

Perpetual spring would actually mean no spring at all. No autumn either, perhaps the loveliest of seasons with its bitter-sweet associations. It was once all so simple in Genesis. ‘While the earth remaineth, seed-time and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease.’ But if you read it carefully, that was both a promise and a warning.

Jeremy Mynott

8 February 2023

I’ve had some big game in the garden at night recently – two elephants, three tigers and a leopard for starters. Also a menagerie of smaller creatures, including: a fox, puss, kitten, mouse, some tabbies, several hummingbirds and peacocks, lots of pugs and even a shark, though I’m still hoping for my first lobster and goat. No, this isn’t some radical Shingle Street rewilding exercise; these are just a few of the weird and wonderful names of the moths that grace our gardens every night and lurk unseen in them by day. Mention moths and most people immediately think of clothes moths. These are the moths referred to in the Bible, where we are advised not to lay up our treasures on earth ‘where moth and rust doth corrupt’. But there are only two kinds of clothes moths in the UK – really tiny ones, and in any case it’s their larvae (caterpillars) that cause the problem. You might be amazed just how many other kinds of moths there are out there – some 2,500 kinds in the UK as a whole. And with the expert help of Nick Mason, our local moth-er (don’t forget the hyphen), I’ve found a remarkable tally of over 350 different species just in my own back garden. Most moth species were first identified and named by naturalists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and they bequeathed to us this wonderful lexicon of names, not just the animal ones mentioned above but a whole treasure-house of footmen, quakers, wainscots, rustics, lutestrings, carpets, fanfoots, tussocks, darts and daggers. There are also some wittily intriguing ones like the Uncertain, the Suspected and the Confused. How splendid to know that we have living amongst us a Setaceous Hebrew Character, a Pebble Prominent and the lovely Merveille du Jour.

Moths matter. They’re an index of the health of our environment. Readers of my generation will remember the ‘moth snowstorms’ we used to get years ago on our car windscreens. Not anymore. Despite the captivating diversity I mention above, moth abundance has declined dramatically in recent years. Disastrously too, since moths are a key part of the larger eco-system: they pollinate plants, and their caterpillars are a crucial food-source for birds, just as the adults themselves are for bats and for birds like our heathland nightjars. Hence the elaborate camouflages they adopt – as in the featured Peppered Moth blending perfectly with the blotches on my paving.

Moths are also beautiful when you see them close-up. Take a look at the ones on the Shingle Street website under Gallery.

Heretical to say it, but they make the gaudier butterflies look almost vulgar.

Jeremy Mynott

August 2022